|

|

The gcc compiler we all rely on when developing programs for Linux is a standard recognized throughout the entire UNIX world. It's fast, it's straightforward, and it compiles standard C (or C++ for the g++ compiler). But anyone who has written a large makefile knows it isn't a complete development environment by itself. With the advent of some serious tools like Code Fusion and Source Navigator from Cygnus, developing large projects with multiple programmers is getting easier all the time.

Rather than use these tools, however, many professional software developers rely on Rapid Application Development (RAD) products to design, prototype and code applications. Many of these applications revolve around database access; many are created by an organization for internal use or by consultants for vertical markets. These might be billing or database access systems, customer support systems, or pieces that integrate existing web services so all employees can access data using a browser. The issues facing these internal developers are different from those that face someone creating a ``boxed product'' or a standard open-source project for eventual public consumption. Three examples of these issues include very tight deadlines, a need to integrate with existing IT infrastructure, and a need to run on multiple platforms running in an organization.

The process for completing an internal project might look something like this:

The problem with so many of these internal projects is that after a lot of work has been put into the planning step, the prototype and development take so long and cost so much that the whole project may become unworkable (or at a minimum, go way over budget). Part of the problem lies in converting a plan into a prototype, or a prototype into a working program. Other problems often revolve around a lack of appropriate tools or talent, or the need to create the program so that it runs on multiple platforms (or the Web--which brings a separate set of challenges). RAD tools are the solution many developers look to. These developer tools combine a graphical interface, database access and additional tools to help code, debug and deploy an end-user-oriented application.

While a few high-end tools have been available on Linux for a while--some for $10,000 or more per developer--those needing RAD tools normally didn't consider Linux. (One promising tool, Borland's Kylix, is still in beta testing.)

A recent entrant in the field of Linux software development is Omnis Studio from Omnis Software (http://www.omnis-software.com/). Though this company and product have been around for over twenty years, they began shipping a Linux product just last year. Fortunately, the maturity of their products and the depth of the feature set have carried over very well to the Linux port. Omnis Studio takes a Java-like approach to software development that creates a single cross-platform program in a very powerful graphical development environment.

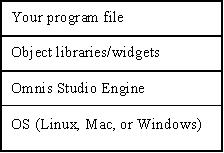

Omnis uses a run-time engine to both develop and execute programs. If ``editing'' is enabled in your license, you can create new programs; otherwise, you can run only existing programs. Amazingly, this engine (without the libraries your program may require) is only about 1MB. Both the small size and the execution speed of Omnis Studio applications are surprisingly good, given that this is an interpreted environment. Engines that let you create and execute Omnis Studio programs are available on Linux, Windows and Macintosh. To show the flexibility of the technology behind this product, consider that you can develop a program on Linux, make changes to the same program file on a Windows system (running a developer license of Studio), then run the newly altered program on a Macintosh. You can think of the ``program'' as a script that can be run or edited on any of the platforms. Figure 1 shows the architecture of the product.

Longtime users of both Omnis and other tools (Java or Visual Basic) have told me that Studio requires about 20% of the development time of Visual Basic because of the automation Studio includes. Some of these automation features are things like auto-typed variables which are tokenized throughout the project, and single-file projects that collect all relevant information in one place.

Omnis Software considers Visual Basic to be the main competitor to Studio. The good news is that with Studio, internal development projects which would have required Windows workstations or an expensive UNIX RAD solution can now be developed on Linux and executed on any system with a browser. The interface to Studio is shown in Figures 2 and 3. It's a challenge to capture many features in just a screenshot or two, but you can see some of the widget palettes, properties, notebooks and method editors. Standard tools like buttons, lists, menus and text are included, all tied together for quick results. A scripting language called ``notation'' is used to add code to objects, but in my experience, little coding is needed compared to something like Visual Basic. The entire product is object-oriented, with object inheritance and powerful class libraries.

Figure 2. Omnis Studio Interface

Figure 3. Omnis Studio Interface

Two of the most time saving widgets included with Studio are those for database access and web-based applications.

The Database widget creates a connection to a database within your application, allowing you to view, add and delete records. The database can reside on several types of servers including Oracle, Sybase, Microsoft SQL, IBM's DB2, or any ODBC-compliant database server. All the details are taken care of for you; just define a form for the fields to appear in, and code the actions to take on each piece of data that an end user works with.

Because the development platform is also the run-time engine, you can use the database widget in real time to manage databases as you develop an application. You can copy schemas (record layouts) between tables or into your program, or move data between tables located on different database servers (even if the servers are running different database products).

Omnis Studio also includes a plug-in you can add to your browser so that any application you write can be used within a browser over the Web. To ``webify'' any application you've created, just add a few widgets to the application. This does require you to include the Studio application on the system running the web server (Apache on Linux or IIS on Windows), plus you must add the Studio plug-in to each client's browser, but the ability to rapidly turn Linux into a true application server may be reason enough for some developers to give Studio a try.

The biggest advantage I've seen with using Studio is that the prototype I create using the application wizard, standard widgets and a little bit of scripting is a working program which I can begin testing. If my ``prototype'' requires some tweaking to fit the project description or client requests, I can do that immediately and even re-deploy the application via the Web to people who are already using it. Automatic updates is a feature not all developers will need, but creating a prototype that with a little polishing turns into a working program is something any overworked developer can appreciate.

You can get a full copy of Omnis Studio for $149. That doesn't include any printed manuals, but all of the documentation (several thousand pages) is included on the CD. Separate printed documentation sets are available if you need one. Several free downloads are available from the Omnis Software web site, including additional database support modules, an evaluation version of Omnis Studio, and the web plug-in (so you can try existing applications at the web site using your browser). A limited edition of Omnis Studio 2.4 is also included with Caldera's OpenLinux 2.4 eDesktop product.

Okay, so I'm very impressed with Omnis Studio. But a couple of flags need to be raised as well. First, the learning curve with this product can be steep. Maybe this is best expressed as ``easy to understand, difficult to master'', which of course is much like Linux itself. Studio uses a proprietary scripting language and a number of ``wizards'' and widgets of its own design. All this is similar to products like Visual Basic, but Studio has its own way of doing things. If you're willing to put some work into learning the product, you can generate amazing results; if you just tinker, you're unlikely to even scratch the surface of what the product can do. Omnis is working hard to make it easier to learn their product, and they have a terrific group of experienced developers who help each other via the Net. In addition, the documentation is solidly written and full of complete examples, included on the product CD-ROM.

The other big catch is that this is true commercial software. It comes with a heritage of big UNIX and Windows installations at Fortune 500 companies. Although Omnis has lowered their prices significantly as they enter the Linux market, the product is really intended for internal or consultant-oriented development at medium to large companies. To that end, you must pay a run-time engine license fee for each workstation on which you deploy the application you write. It's a small fee, on the order of $10, but it's certainly not open source. On the other hand, when you're under the gun to create a powerful program with a ridiculous deadline, it's a price you may be happy to pay.

Nicholas Wells (nick.wells@lineo.com) is the director of technical services at embedded Linux vendor Lineo, Inc. He has published about ten books on Linux, KDE and the Web.